Teaching Diversity

Local educator, author and graduate student Ia Xiong takes pride in

teaching the distinction between cultures

By CHHUN SUN

At first, Ia Xiong hated school. And it’s hard not to blame her.

She wasn’t considered the brightest kid in class. She was slow to

understand the subject matter. So she tried to avoid class, but couldn’t

go very far, especially when class was held in a refugee camp in Thailand,

where she lived.

And then there were the slaps on the hand, punishment for not answering

correctly.

“I don’t like that, either,” she would say to her teacher.

“I don’t get it, I just don’t get it.” But that

excuse didn’t get her far.

|

As vice principal of Centennial Elementary, Ia Xiong enjoys teaching

students the importance of diversity. The graduate student will

speak tonight at 6 p.m. in the Henry Madden Library as part of the

Friends of the Madden Library program. Photo by Joseph

Hollak |

Then, at age 12, she came to America with her family, a storybook dream

of seeking a better life and escaping her war-torn country. America was

where she was told she could go to school for 10 years, at no cost. It

was a bluff at the time. But it was motivation to learn everything as

quickly as she could.

Xiong found learning easy and her teachers were supportive of her efforts

in learning another language.

“When I started going to school, no one embarrassed me,” she

said with a smile. “In fact, no one hit me.”

Years later, school no longer gives her the jitters. How could it?

She goes to school everyday as the vice principal of Centennial Elementary.

At the school, she’s an instructional leader for about 800 students,

including Hmong children like her, guiding them through the same adjustments

she had to endure.

Not only does Xiong discipline student, but she also teaches them the

importance of diversity. And this is one of the topics she will share

today at 6 p.m. in the Henry Madden Library as part of the Friends of

the Madden Library program.

She will also discuss her achievements.

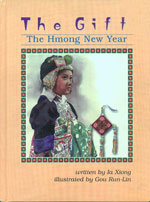

In 1992, Xiong became the first Hmong-American to teach in the Clovis

Unified School District at Sierra Vista Elementary. While she was teaching,

she found the inspiration – from her cultural background and the

Hmong children she knew – to write a book called “The Gift:

The Hmong New Year,” a way to let Hmong children know the importance

of their culture.

After

receiving her bachelor’s degree at Fresno State and her master’s

degree in school administration at Fresno Pacific University, she transferred

to the Fresno Unified School District in 1997. Now she’s earning

her doctoral degree at Fresno State, hoping to fulfill a goal to teach

at the college level, because she said she would eventually not have the

energy to discipline children much longer. After

receiving her bachelor’s degree at Fresno State and her master’s

degree in school administration at Fresno Pacific University, she transferred

to the Fresno Unified School District in 1997. Now she’s earning

her doctoral degree at Fresno State, hoping to fulfill a goal to teach

at the college level, because she said she would eventually not have the

energy to discipline children much longer.

“I can do it now as a young person,” she said, “but

when you get older, that energy is going to dwindle, so I need another

door to build information. I need an open door that I can access.”

She can access this door of opportunity because of the lessons she learned

from her parents.

What she remembers from her childhood is the constant moving. She was

taught early on to wake up at the sound of her parents’ voices,

because nothing was guaranteed in the refugee camp. She has learned that

when emergencies arrive, a family needs to stick together – a cultural

tradition that has carried over to the U.S.

Those are the kinds of differences she has noticed between American and

Hmong traditions.

Her parents always told her that by the time she turns 20, she should

be ready to start her own life.

That meant a family, an education, a job and a family. Those were the

expectations.

And she’s met them.

Even now, at 35 years old with all her achievements, her cultural expectations

are still catching up to her.

“To the Western culture, it’s not old at all,” she said.

“But to the Eastern culture, you’re hitting middle age. That’s

one example of the differences.”

But like in her childhood, she keeps moving.

The children who she sees every day is what makes her move forward, even

though she works 10- to 14-hour days. She said she spends most of her

days disciplining kids, resolving fights and behavioral problems. But,

she said, seeing a child change in front of her eyes is worth her efforts.

“It’s self-esteem for us, telling us we’re doing something

good,” she said. “In a job that requires such long hours,

you have to like your job. I do it for self-esteem or for something else

other than money. If you calculate the work money-wise, it doesn’t

compare.”

That’s one attitude she’d like to carry back home one day.

She has visited Thailand three times since settling in America.

The first time was “to touch base with my soul,” she said.

The second was to get a close look at the differences in the Hmong culture

from the one in the U.S. The third was to take an inside look at the educational

system.

With that attitude and her expertise in education, the chance to go back

home and teach may not be too far away.

|