The United States of America is not a direct democracy.

However, the popular phrase “we are a republic, not a democracy” is misleading.”

Democracy, broadly speaking, refers to a system where power is vested in the people. This includes both direct democracies, where citizens vote on laws themselves and representative democracies, where citizens elect officials to make decisions on their behalf.

A republic is a form of government where the country is governed by elected representatives and an established set of laws, usually outlined in a constitution.

The United States is both a representative democracy and a constitutional republic. It’s not an either-or equation.

Many political theorists like to stress that the Founders were wary of pure democracy because it could lead to “mob rule” or the unrestrained “tyranny of the majority.”

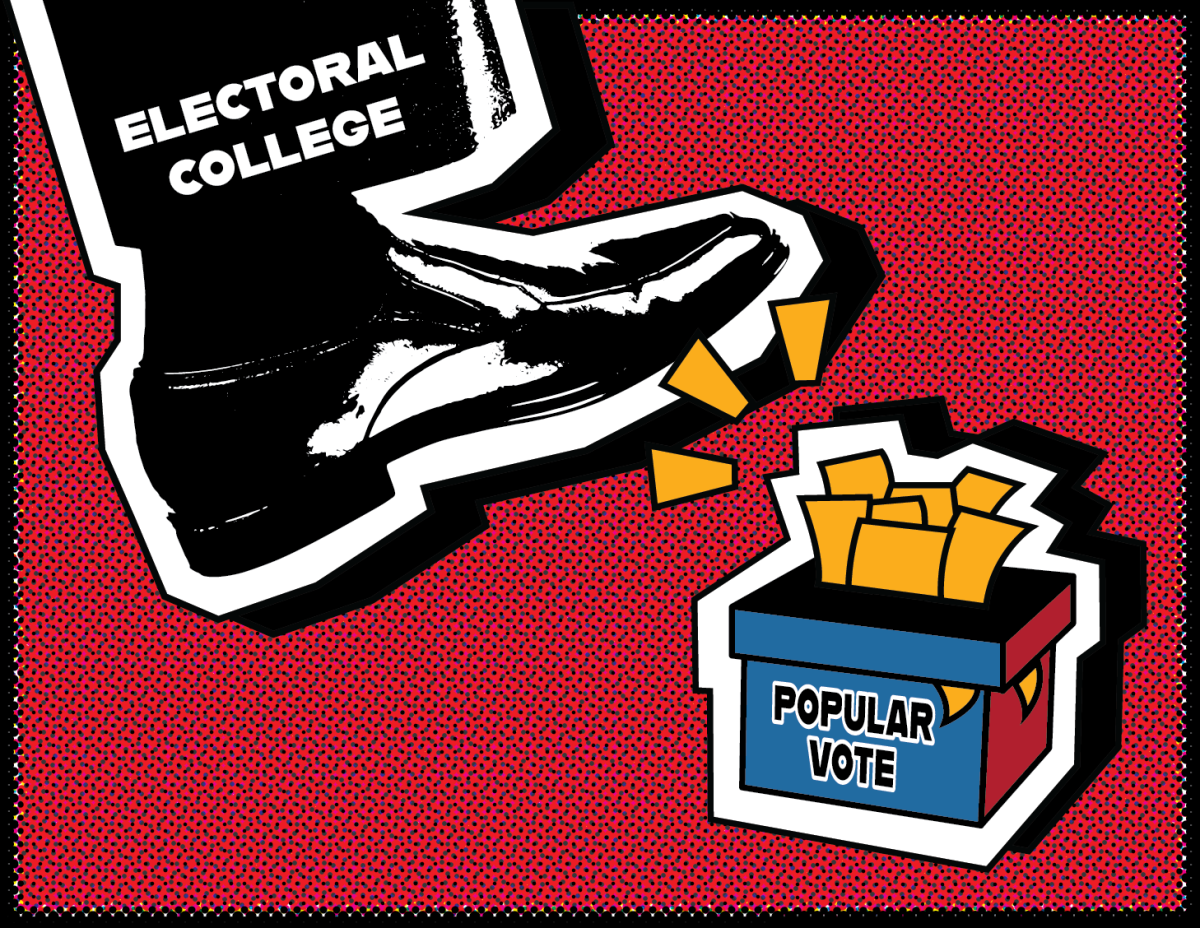

When it came time to erect the tent poles of the fledgling nation at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the Founders’ desire to prevent the potential pitfalls of majority rule led to the creation of the Electoral College, one of the most notoriously undemocratic features of our government.

Until it is abolished, it risks empowering a tyrannical minority to shape the nation’s future instead.

Even the Founding Fathers weren’t fond of it. After months of intense squabbling, it emerged as a compromise between those who wanted Congress to choose the president and those who favored a democratic popular vote. Instead of choosing one or the other, they decided that the responsibility for determining the next president would fall to electoral intermediaries. These “electors” would not be chosen by Congress or directly elected by the people but appointed by the states to cast the actual ballots for the presidency.

Determining how many electors each state would have proved equally contentious. In 1787, about 40 percent of the Southern population were enslaved black people who could not vote. This became an issue because, without counting them, the South would have significantly less power than the North.

To make it more favorable to these slave owners, they ultimately decided on the “three-fifths compromise,” in which three-fifths of the enslaved black population would be counted toward allocating representatives and electors.

This is why it’s difficult to make a democratic argument in favor of the Electoral College—it was conceived as an inherently undemocratic institution.

Rather than ensuring fair representation for all, it was designed to balance political power in favor of Southern states, where large populations of enslaved black people were denied rights and freedoms, significantly skewed population counts. It was, in effect, a form of affirmative action—one designed to protect the interests of white plantation owners.

Hundreds of years later, we’re still bound by a system created to serve such unjust goals.

Every state receives a minimum of three electoral votes, based on its two senators and its House representatives (which vary by population). As a result, Washington, D.C.—despite having a larger population than Wyoming—has the same three electoral votes but no voting representation in Congress. This setup gives more weight to voters in smaller states than to those in larger ones—the ones with more cows than people.

The Electoral College is also vulnerable to targeted efforts to sway outcomes. Before President Trump’s riled-up supporters stormed the Capitol, Republican legislators attempted to pressure Congress to overturn Biden’s victory by challenging electoral votes from key battleground states. Reversing the will of millions of voters would have been far more difficult without the Electoral College system.

There are better, more democratic electoral systems available. Introduced in 2006 and adopted by seventeen states and the District of Columbia, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is an agreement to assign all participating states’ electoral votes to the national popular vote winner. It only takes effect once enough states join to ensure the popular vote winner becomes president. It would make every vote meaningful.

Ranked-choice voting has also proven to be a viable alternative in Alaska. Voters rank candidates by preference; if no candidate wins a majority, the lowest-ranked candidates are eliminated, and votes are redistributed until one achieves a majority. This system encourages diverse candidates, reduces “lesser of two evils” choices and ensures broad support for the winner.

The Electoral College has outlived its purpose and is now amplifying inequalities rather than serving the people. To honor our democratic ideals, it’s time to replace them with a system that truly reflects the will of the people and shields us from the tyranny of a few.