Trigger warning: This story features sensitive topics.

Judithe Hernández, a prominent Chicana artist who is the fifth and only female member in Los Angeles art collective, Los Four, has been showcasing the brutalities that happen to Mexican women through art.

In the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, hundreds of women and girls were victims of femicide in Juárez, Chihuahua, across the border from El Paso, Texas.

Femicide is defined as an intentional killing of gender-related motivation.

According to Amnesty International, the number of femicides occurring in Mexico during the 90s and early 2000s was 370, but according to Ni Una Mas, an activist organization from Mexico, that number was 500.

As recent as 2020, there have been 3,723 killings of women reported, with 940 of those being registered as femicides.

“Today, I use femicide in recognition of the fact that while many of these victims are murdered because they were female, there is also a systemic component to these unsolved cases,” said Charlene Villaseñor Black, a professor of Chicana/o studies at the University of California Los Angeles.

On Nov. 7, the Art History club of Fresno State invited Villaseñor Black for a lecture on Hernández’s “Juarez” collection and its correlation to necropolitics. Hernández’s artwork and the relation to necropolitics in the “Juarez” collection is imagery that showcases the use of social or political power that dictates how people may live or die.

“In necropolitics, some lives are worth more than others. Some people can be exploited and eliminated,” Villaseñor Black said during the artist talk. “Gore capitalism or related concepts articulated by transfeminist Sayak Valencia, builds on and is related to necropolitics, but is located specifically in border regions, such as Tijuana or Juárez.

Luis Gordo Peláez, an assistant professor in the art history department, said that artists tackling sensitive topics build connections with the past and with culture.

“I think this [Hernández’s artworks] is good because [it’s] connecting something that is very relevant now in our present [time] and with also iconography and content from the past. It goes back to the culture and history of Mexico as well,” Peláez said.

The first example of necropolitics found within Hernández’s artworks is from 2007. The seriality artworks showcase the femicide of female factory workers in the “Maquiladoras,” or factories.

Since 1993, 400 female employees at tariff and duty-free factories in Juarez have been killed with hundreds of others still missing.

The series, which includes “Mano de Sangre, (Hand of Blood)” and “The Weight of Silence #12” displays a repeating figure enduring different forms of torture, with the use of red handprints signifying the bloody traces of the women’s murders.

During this time, the North American Free Trade Agreement Treaty went into effect in January 1994, allowing Canada, Mexico and the USA to build manufacturing plants in Juárez.

In another artwork titled “La Frontera (The Border),” Hernández utilizes the same figure, this time with a much more intense background and direct symbolism of barbed wire around the subject’s neck. Her eyes are shadowed, which can be interpreted as her life being taken away from her.

“It’s asking us to directly confront these women’s humanity, to look them in the eye, in their faces, and think about what’s happened. So she does use that frontal pose a lot and it is very confrontational,” Villaseñor Black said about the repeated figure in the two artworks.

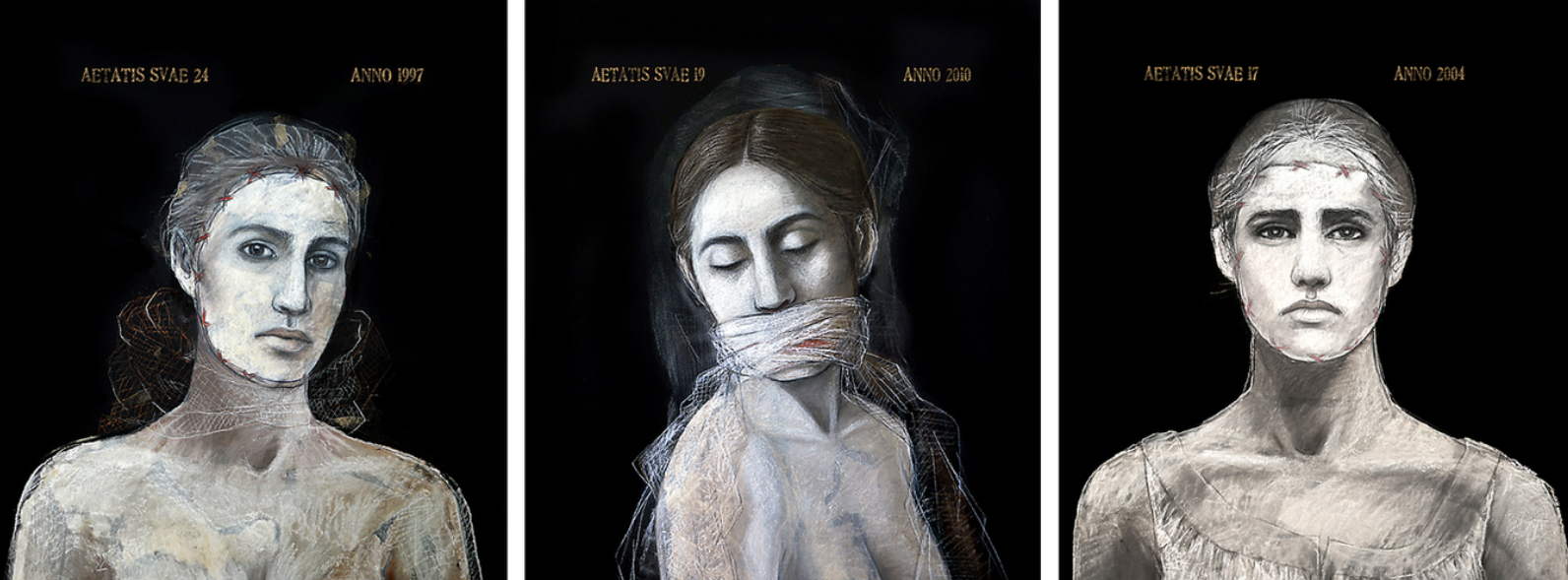

Hernández’s goal for the “Aetatis Suae” three-panel artwork, or triptych, is a generalized representation and serves as a memorialization of Mexican women’s deaths.

The triptych is black and white with the bold color of red representing scars and the gruesome telling of a mask stitched onto one of the subject’s face. The figure on the left of the triptych has a visible interloping of a textile wrapped around her neck while the subject in the middle has her eyes shut and a scarf wrapped around her mouth.

The theme of barbed wire returns in “Juárez: La Ciudad de la Muerte (The City of Death).”

Hernández portrays a feminine subject with green skin and red hair. Her pose is similar to the iconography of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion. Above the subject’s head hangs papel picado, paper decorations typically used for celebration of Day of the Dead. Instead of the traditional patterns found on the papel picado, the patterns form the words, “mujeres, feminicidios, Juarez and 500 muertas” (women, femicides, Juarez and 500 dead women).

“She’s depicting the female nude but she makes their bodies unreal colors. She’s trying to prevent viewers from objectifying them as beautiful so I’m guessing the [red] hair is similar,” Villaseñor Black said.

In the last series of artworks, Hernández takes a more slightly hopeful approach to the women who had their lives taken by femicides.

In a collection of six artworks, each piece utilizes a “dreamscape” or a background of fantastical backdrops that set the subject in the forefront of the artwork. Albeit a bit peaceful to the eye at first, the artworks reveal a much darker backstory than meets the eye.

In the first example of the pastel artwork collection is “Santa Desconocida,” a female subject is displayed in a dark take of a reclining Venus pose. The subject is laid upon cacti with her eyes closed, only able to muster enough strength to hold her hand up. Her clothes are tattered and an ominous red hand and red ribbon are tied around the “Santa’s” neck, giving the viewers a message that her life was taken by the red entity.

“The genre [of dreamscapes] usually asks us to consider the vitality of feminine youth and beauty and Hernández’s reclining figure here refuses that desire,” Villaseñor Black said about the artwork.

Another harrowing example from the series is “Juarez Quinceañera,” which presents to viewers a story of the taking of a girl’s rights to passage of becoming a woman.

The pastel on mixed media paper showcases a young girl in front of a pink background. On each side of her are bloody handprints that tell the viewers that something wrong has happened. Dressed in a black dress and holding two callas, the girl’s face is replaced by the iconography of Indigenous deities.

The iconography derives from Mayan sculptures and a very specific example of a green effigy mask of the Aztec moon goddess Coyolxāuhqui.

The story behind the Coyolxāuhqui green mask derives from the tale of her brother Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, beheading her and throwing her body down the side of Coatepec, the “Snake Mountain.”

“In this way the artist traces the misogyny, motivating these murders back to the colonial era, to the imposition of European attitudes toward women and racism towards Indigenous women in particular,” Villaseñor said.

Grace Morrow, president of the Art History club, said that art is used to reach the masses, even more so with the use of social media.

“It’s important to share that [sensitive topics]. It’s important to shed light to issues that might not have been shared before and to give those artists and that artwork a platform to share on these bigger global issues,” Morrow said.

The Art History club will host its next artist talk with Miguel Valerio on Thursday, Nov. 16, at 5 p.m. in Music 160. Valerio will be presenting Afro-Brazilian religious architecture and art.