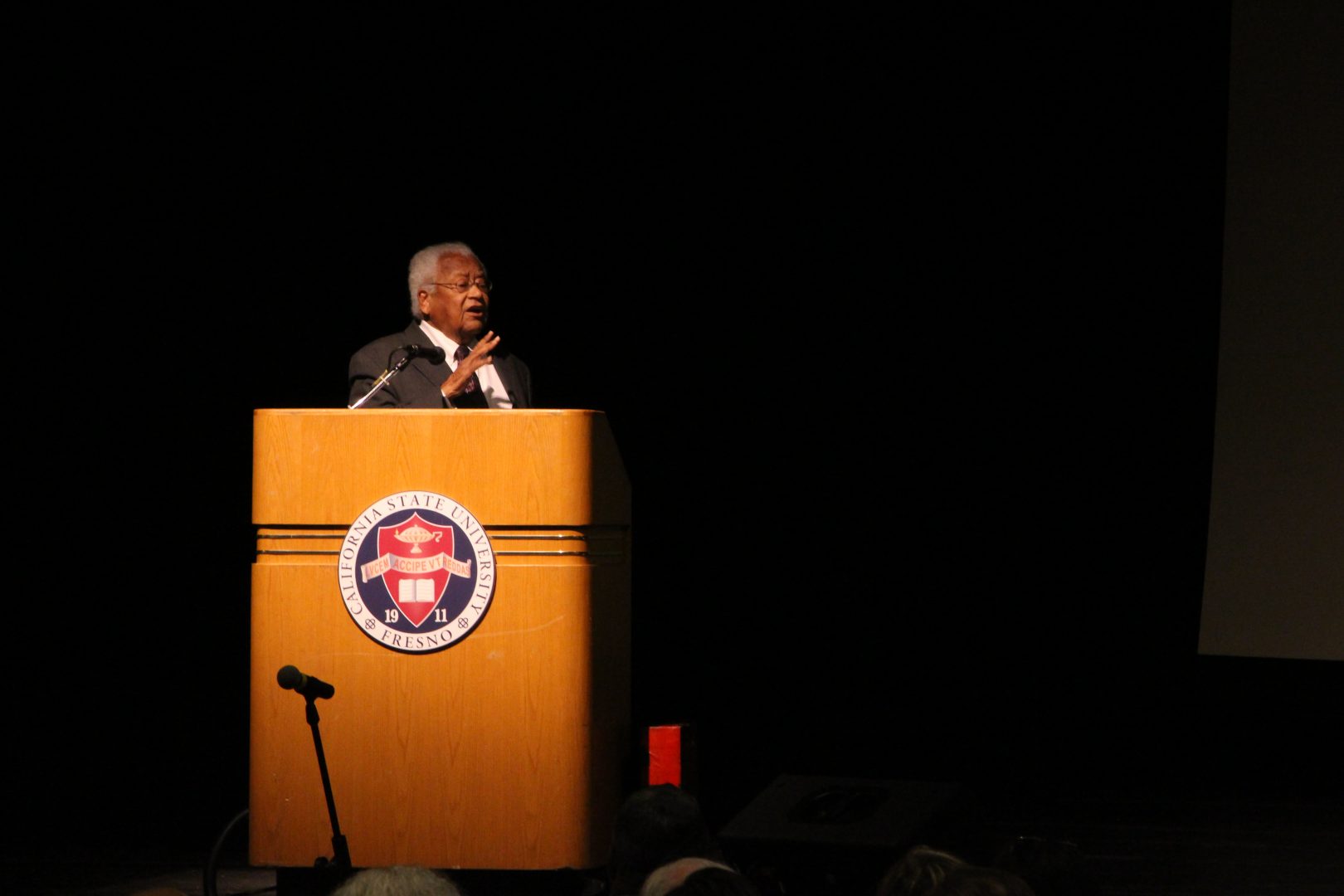

Fresno State hosted a webinar on Wednesday entitled “Gandhi, the Civil Rights Movement and the Continuing Struggle for Justice and Peace,” involving renowned civil rights scholars Rev. James Lawson, Vinay Lal and Dianne Dillon-Ridgley as panelists.

Veena Howard, an associate philosophy professor and Gandhi scholar, organized the webinar, which focused on historical connections between Mahatma Gandhi and leaders of the civil rights movement, along with the current struggle against racial inequality, injustice and police violence in America.

“This webinar is to educate ourselves, learn from our past, and history. It’s [the history is] not perfect, it has flaws,” Howard said. “We don’t want to shut any voice and we don’t want to bring more misunderstandings in the world.”

The panelists heavily discussed the controversy surrounding the classification of Gandhi as a racist due to Gandhi’s earlier writings.

Fresno State was the center of this controversy in June when a petition calling for the removal of a Gandhi bust in the Fresno State Peace Garden gained thousands of signatures and national attention.

The petition cited Gandhi as having racist ideologies against Black Africans, as well his remarks toward minority groups like low-caste Hindus and women as reason for the removal of his bust.

“To try and mark him [Gandhi] as something different from that [a pioneer] is a crime against humanity,” Lawson said.

Lawson believes that those who classify Gandhi as a racist should be classified in the same category as looters. He said that there are criminal elements on display and they are using the cover of a movement to put their point of view on display.

“They are the enemies of all movements in the United State for social justice, political justice, gender justice, cultural justice and ending our culture of violence,” Lawson said.

Lawson said that there were many prominent Black leaders who made deliberate efforts to meet Gandhi and were influenced by the Gandhian perspective of love, nonviolence and tactics of social change.

“These men are all men who knew racism in the United States at its core,” Lawson said. “Yet, they saw Gandhi as a pioneering figure in the world who gave them hope for changing this country.”

Lal, a professor at UCLA and writer of numerous books on the topic of Gandhi, addressed the interpretation of Gandhi’s thoughts toward Black Africans and women in general.

Gandhi has been criticized for not including Black people in his struggle during his time in South Africa. Also, he has been heavily criticized for his use of the word “Kaffir”, a derogatory and pejorative word, to describe Black Africans during his stay in South Africa in the early 20th century.

Lal said that people must reflect upon the fact that Gandhi never undertook a struggle on behalf of someone, a group or community, unless he was asked to do so. He also argues that if Gandhi would have taken up a struggle for Black South Africans, critics would have said, “How dare he speak for a Black person.”

As for Gandhi’s use of the term “Kaffir,” Lal said that it referred to several classes of people. He continued that the term did not have the pejorative connotations it does today, and. even so, Gandhi’s ceased the use of the term in 1913.

“I think we have to understand the historical circumstances under which he used that word [Kaffir],” Lal said. “Because I can assure you … the historical record of how this word has been used, at that point in time it did not have, generally speaking, the pejorative connotations it would begin to acquire later on.”

“We can do a very detailed analysis to understand how Gandhi’s views on the question of race began to evolve. In some ways, he is following the conventional views,” Lal said. “In some ways, he is actually setting the trend for changing our thinking on the question of race.”

An argument that Lal believes can be made is that the way in which our way of thinking on race has evolved is owed largely to Gandhi. This is an argument that is contrary to the one made by those who consider Gandhi a racist.

“I come back to the point that those, what some scholars are calling the radical fringe, do not have a solid argument for the position that Gandhi was a racist,” Lawson said. “They want to deprive the movement and the major struggle against racism and economic deprivation and sexism and violence. They want to cause that movement to fracture and disappear.”

Lawson said that those fringe groups do not want to join the focused struggle that Gandhi led during his lifetime. He said that in almost every struggle he has been a part of there has been an outside fringe group that wants to use the campaign for their own purposes.

Fresno State President Dr. Joseph I. Castro also addressed the controversy surrounding the Gandhi bust in his opening remarks. He said, “We applaud those who call for a clear-eyed look at history and the individuals that shape it. We also urge everyone to consider the overall significance of each individual’s lasting contributions to a just and fair society.”

When it came to the topic of the current movements in America, especially those in response to police brutality, Dillon-Ridgley reflected upon a time when she was asked in 2000 what word would be used to describe this century.

Dillon-Ridgley said her answer was “justice.” She believes that all of the social action going on in the last year is leading toward justice.

“We are at a racial reckoning,” Dillon-Ridgely said. “To me it is like we ripped off the bandages and the scars, and the transparency of truth and sunlight is allowing for all of the distortions and lies to be cleansed. To be exposed.”

Lawson, who is a pioneer in nonviolence and sit-ins, spoke on the current climate of police brutality and how the United States is experiencing “the largest and finest nonviolent movements in U.S.A history.”

“Over 700 cities have had these demonstrations for the discussion of how in a democracy the police should operate. A discussion that the nation has never had,” Lawson said. “Also, a discussion about why we as a people in [the] USA have continued to allow police to be executioner[s] of our citizens without question.”

Lawson addressed that in the midst of the current nonviolent movement there are elements of violence. He said that America’s culture is a violent culture and the police represent that culture.

But, Lawson expressed criticism toward Antifa and other organizations that he categorized as “anarchist.”

“Anarchist groups think that little bits and pieces of violence, sabotage and fighting the police is important to social change,” Lawson said. “They are more a part of world culture of violence, and then they are a part of any movement for the emancipation of life from the shackles of hurt and brokenness.”

Lawson believes that a nonviolent paradigm is needed for the United State to move from violence as a power of social political dominance to nonviolence. He said what is happening primarily with nonviolent campaigns today will make that change.

“In the meantime the movement for a different United States of America through nonviolent struggle, through nonviolent theory and tactics must become the mainstream,” Lawson said. “Every movement of power is a minority movement, but the discipline of nonviolent work is the thing our activism in the United States needs more than anything.”

Lawson said from what he has experienced with being around Black Lives Matter (BLM) leaders, they are emphasizing the nonviolent character of their demonstration.

“While they repudiate the radical fringe groups, as well as the police in their violence,” Lawson said. “They call the marchers to keep the discipline of nonviolent work … both in their gesture and walking and in their own hearts.”

Dillon-Ridgley discussed the first time she met Patrisse Cullors, one of the founders of BLM, a few years ago and how there were some reservations on how BLM was going to approach creating a movement.

“She [Cullors] came into this discussion with such grounding in love,” Dillon-Ridgley said. “Patrisse spoke about being attacked and traveling with a guard to keep her safe, and yet everything in her was a message of love.”

“My favorite Alice Walker book is ‘Anything We Love Can Be Saved.’ We can save this country. We can save ourselves. We can save our souls,” Dillion-Ridgley said. “We must do it through nonviolence and we must do it through love.”

Written with a contribution from Andrea Marin Contreras