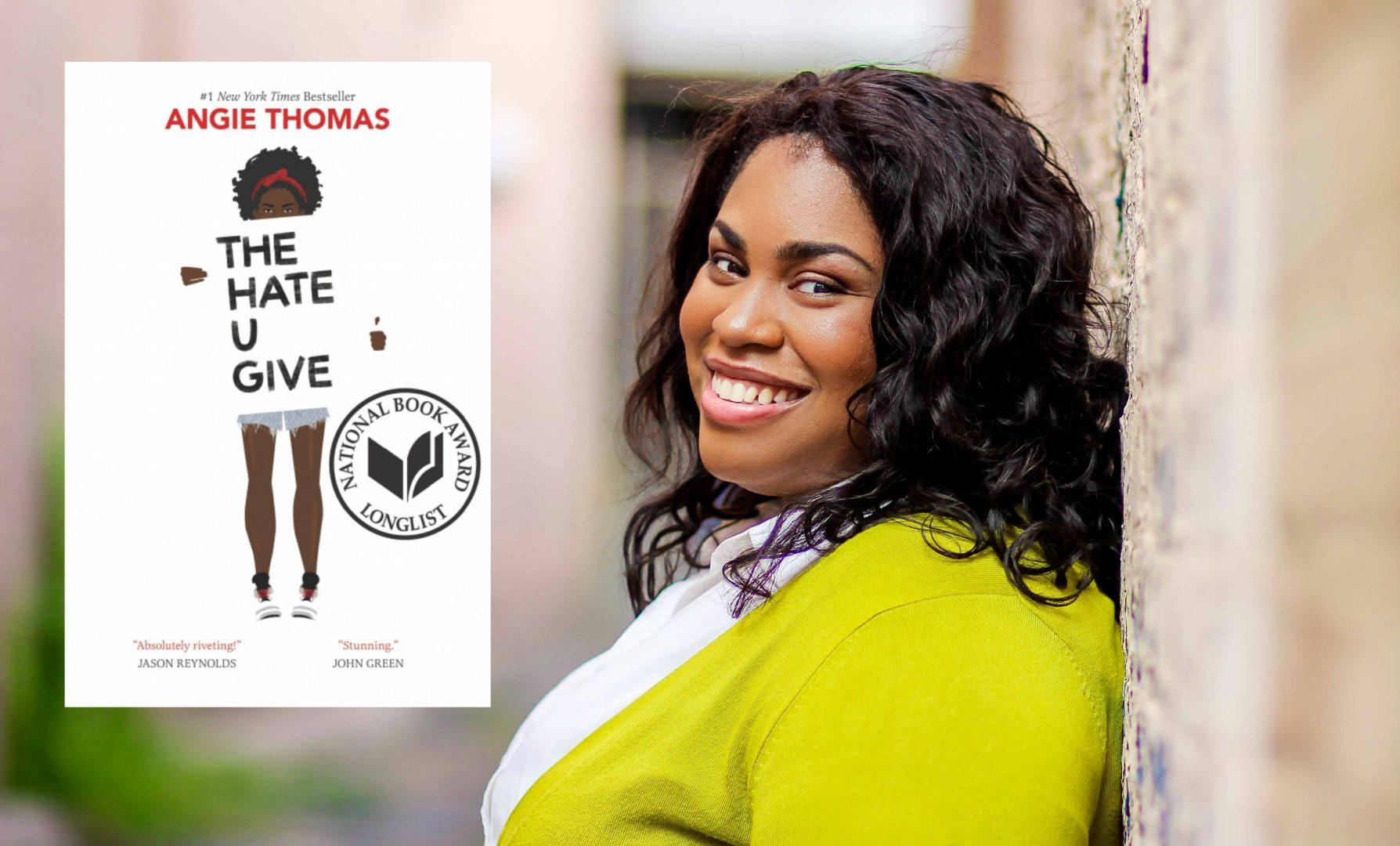

A #1 New York Times Bestseller.

A William C. Morris Award for a debut author writing for teens.

An Odyssey Award for excellence in audiobook production.

A Printz honor.

A Coretta Scott King Book Awards honor.

A film adaptation.

“The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas might be one of the best books I’ve read — ever. Based off the buzz alone, I knew I would enjoy it and learn from it.

Starr Carter, the book’s 16-year-old protagonist, struggles to balance the two worlds she keeps separate — the poor black neighborhood where she lives and the fancy suburban prep school she attends.

Both of Starr’s worlds begin to crumble and clash after she witnesses the police shooting of her childhood best friend, Khalil. Khalil was unarmed.

In the fiction book, Khalil’s death quickly becomes a national headline, and Starr listens as everyone around her calls him a drug dealer, a gangbanger and a thug. Being the only witness that night, she quickly realizes it’s up to her to decide on what she should – or shouldn’t – do or say.

Thomas addresses today’s issues of racism against blacks and police violence with determined honesty, care and intelligence. Readers won’t be able to put the book down.

As a Latina, it is not my place to speak about the black experience (or any other oppressed group’s experience that isn’t my own) as if I understand it. But I do feel it is my job to do my best to make genuine attempts to understand it so I can be an ally.

“The Hate U Give” is a great place to start.

Thomas discusses racism, police brutality, drugs and gangs, but also interracial romantic relationships, family, friendship and community. Class, social expectations and pop culture are also thoroughly incorporated into the story.

One of the most reassuring parts in the book, for me, centered around Starr and her two best friends, Maya and Hailey.

This particular section in the book discusses removing people from your life who won’t take the steps to understand and accept who you are and what you find important.

It’s not uncommon to be a part of a minority and grow up with someone who makes racist jokes or uses a word that you have to laugh off because everyone else is laughing. Soon, it becomes normal, but you always feel uneasy about it in the back of your mind.

Starr, who is black, and Maya, who is Chinese, face this situation with Hailey, who is white. Hailey makes little effort, if any, to understand their circumstances in society. She shrugs the situation off, telling them to get over it. Though they have been best friends for years, Starr and Maya eventually end their friendship with Hailey.

Thomas is basically saying: If someone in your life is willing to brush aside racist remarks that make you feel uncomfortable and they aren’t willing to apologize and change, you do not need to continue to be their friend. Even if there are years of friendship between you, it is OK to end it.

Thomas contrasted Hailey with Starr’s boyfriend, Chris, who is also white. Whereas Hailey is in a constant state of brushing off Starr when it comes to racism, Chris is the exact opposite. He actively tries to understand Starr’s perspective, and he listens to what she has to say.

Thomas also makes sure she placed importance on those who have lost their lives to police brutality. The words of Eric Garner, who was killed by police for selling loose cigarettes, are echoed in the third chapter: “They finally put a sheet over Khalil. He can’t breathe under it. I can’t breathe.”

In the final chapter, Thomas goes a step further and names those who have lost their lives to police brutality.

“It would be so easy to quit if it was just about me, Khalil, that night, and that cop. It’s about way more than that though…It’s also about Oscar. Aiyana. Trayvon. Rekia. Michael. Eric. Tamir. John. Ezell. Sandra. Freddie. Alton. Philando. It’s even about that boy in 1955 who nobody recognized at first ”” Emmett. The messed-up part? There are so many more,” Thomas writes.

Thomas has created a masterpiece that is honest, full of heart and insightful.