A biology laboratory tucked away in the Science I Building at Fresno State is home to several cancer diseases.

And $300,000 in new research funds from the National Institutes of Health are now available to more closely study one of those diseases in particular — breast cancer.

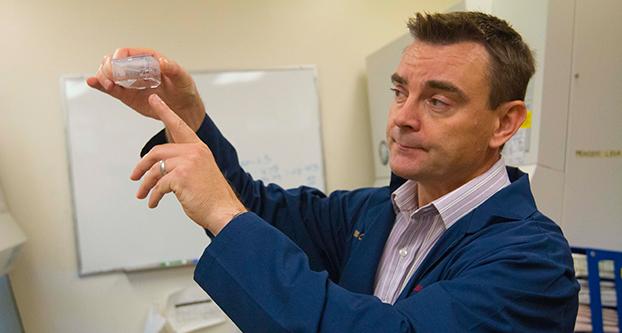

Dr. Jason Bush, a biology professor, works in the laboratory with his undergraduate and graduate research students. He said cancer and cells have been the focus of his research work since about the late 1990s.

During his postdoctoral work, he became fascinated with breast cancer research. It’s led him to new discoveries.

“Cancer cells like to grow,” Bush said. “They like to divide and proliferate abnormally. And in order to do that, cells need building blocks (like amino acids, carbohydrates and fats) and when cells can’t get that, they have to change their metabolism.”

The process is referred to in the science community as “metabolic reprogramming.” And understanding exactly how and why metabolic reprogramming occurs will be the focus of the ongoing breast cancer research.

“If we understand the kind of changes that are occurring (in breast cancer), we might be able to then use that as a strategy to specifically target specific types of cancer cells,” Bush said.

The laboratory will utilize the funds from the National Institutes of Health throughout four years to research and discover potential new strategies for treating the deadly cancer disease.

“Every year in the U.S., 250,000 women are diagnosed with (breast) cancer (and) every year in the U.S., a little over 40,000 women die of breast cancer,” Bush said. “That’s something really significant and we want to have an impact in that by hopefully discovering some new aspects about breast cancer in biology.”

Bush said the research from his laboratory will help guide the larger effort to better understand breast cancer and cancer, in general — a disease that is as old as dinosaurs and includes more than 200 different types.

Students in the laboratory learn to isolate cancer cells and test different types of treatment on them, Bush said. Isolating the cancer cells allows researchers to study the genes, DNA and the proteins that turn a normal cell into a cancer cell.

“If we know where the differences are, then we might be able to develop strategies to exploit those differences for therapeutic benefits with cancer,” Bush said.

In a plastic container, Bush recently placed under a microscope some breast cancer cells that have reproduced. Clearly visible through the microscope lens, the breast cancer cells were among components that make up human blood — like salts, minerals, amino acids and sugars.

Bush said the breast cancer cells are often moved around so they don’t overtake the cells in the plastic dish after it starts to divide.

“They will just continue to divide and divide indefinitely,” Bush said.

When they are not being tested or manipulated in sterile hoods available in the laboratory, the breast cancer samples are kept in an incubator that is set at the temperature of the human body — roughly 32 degrees Celsius according to Bush — so they can live and be available for more testing. Some cells are frozen in liquid nitrogen to preserve them in case the laboratory needs more cells, Bush said.

“The things that we do in my laboratory and in the cancer community in general is trying to understand the early changes — how we can detect it early and what new strategies that we can use to treat it,” Bush said.

He said research funds are critical to advance the knowledge of deadly diseases like cancer, so the search for those funds can never stop.

“I always have to be finding other ways to fund my projects and fund my students and other ways to bring money into the laboratory,” Bush said.

The hopes Bush has for the next four years is that breast cancer becomes much easier to detect. He said he hopes the cancer community can understand the changes in a cell’s metabolism and for scientists to use that knowledge to develop new treatments.

“We might be able to use that or exploit that knowledge to develop some kind of new treatment — new drugs or earlier diagnosis,” Bush said. “If we know there is a change in the metabolism, that might lead to one day a blood test that could detect that change to say that there is cancer in this individual and we catch it at an early stage.”

The earlier breast cancer is detected, Bush said, the better. And though a cure for breast cancer may be years away, Bush said he is already seeing the work of research pay off.

“We are seeing a decline in mortality which means we are seeing an impact,” he said. “We are saving lives because of all of the knowledge and research funds that are going into understanding cancer to improve survival.”

The process for getting the funds was lengthy. Bush first submitted a proposal laying out his specific project or research question. That proposal is then peer-reviewed at the National Institutes of Health using a scientific method, he said. And it’s after that step that science experts review the peer-reviewed work and decide whether funding is deserved.

For someone whose curiosity is abundant — someone who enjoys asking scientific questions and hoping for answers — Bush knows the funding will help his research in many ways.

The biggest benefit, perhaps, could come in the way of passing down the enthusiasm of science and research to students who could be tomorrow’s scientists, he said.

“Science moves forward incrementally, but it does move forward,” Bush said. “It takes dedication. It takes a team effort, and it takes time to be able to develop results and have a story to tell about what we are doing.”