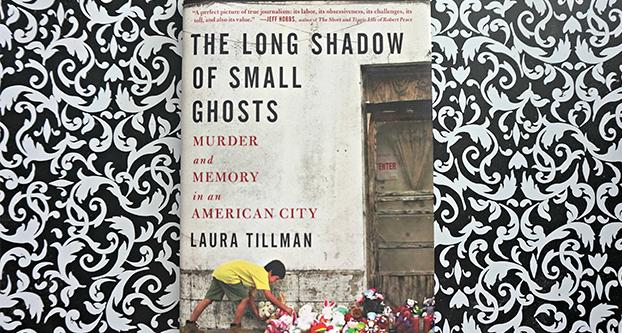

In “The Long Shadow of Small Ghosts: Murder and Memory in an American City,” Laura Tillman perfectly conveys the dedication, the challenges, the emotional toll and the value that comes with being a journalist.

During the early hours of March 11, 2003, in Brownsville, Texas””one of America’s poorest cities””John Allen Rubio and Angela Camacho violently murdered their three young children in their tiny apartment on East Tyler Street.

The building, already run-down, became a reminder to the people of Brownsville of the crime that took place there. The community consensus was that it should be torn down. In 2008, reporter Laura Tillman was on assignment when she first stepped into that building. She was to cover the story of a building the community was hoping would be destroyed.

Little did she know, the visit would raise questions that would lead her on a six-year investigation into the toll a crime like this can have on a community and the way it can make even someone on the outside question their beliefs.

Rubio is a central part of this book. He and Tillman communicated through written correspondence for years while he was in prison. Tillman asked the questions, Rubio answered them. This is how Tillman tries to understand Rubio.

Next to chapter nine, which is titled “Don’t Read This Chapter before Going to Bed” and details the murders of the children, perhaps the most haunting part of this book is something Tillman presents to the reader.

At this point, Tillman was only communicating with Rubio through letters, and she felt meeting him would offer something his letters did not. Rubio initially refused an in-person meeting, but after years of written correspondence with Tillman and 10 years after the crime, he agreed.

Tillman was about to visit death row and this led to her questioning her own stance on the death penalty, a state’s ability to decide who lives and who dies, and how we play a role, whether we are legally involved in the case or not. She presents to the reader: “I, and you reading this, we are compelled to decide if we want to kill John. I need to look him in the face.”

This ultimately leads into a detailed discussion on the death penalty and its history and prompted me to really think about where I stand on the subject.

What I found most compelling once I finished this book was my mental and emotional state in the beginning of the book compared with the end and how similar it was to Tillman’s. I read the synopsis of the book before going in, knew the central focus would be the murder of three young children, and instantly knew I wanted this to be a story I could read and push out of my mind once I finished.

Tillman too, when talking about tragic crimes, felt this way. She wrote, “It was easier to box them up and store them on a mental shelf of humanity’s worst moments.”

As the book progresses, we see Tillman’s investment in the building, the Rubios, and the crime begin to grow. It mirrors our own growing investment. Her emotions reflect our own. As she questions her beliefs, we question ours.

“The Long Shadow of Small Ghosts” is entirely engrossing in this respect and by the end of it, I knew this was not a book I could simply shelve away. The narrative of this horrific crime left me like it left Tillman: emotionally invested and questioning my stance on important social issues such as poverty, mental illness and the death penalty.