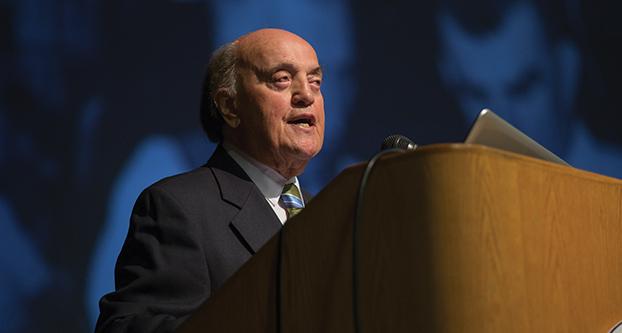

Pulitzer-winning journalist Peter Arnett spoke to a packed crowd Wednesday at the Satellite Student Union on his 50 years of reporting experience — from covering the Vietnam War to his struggles with censorship by the U.S. government.

Arnett, a New Zealander who cut his teeth reporting on the tumult from faraway countries, visited Fresno State on Wednesday to discuss the coverage of the Vietnam War and the role of American news media.

Arnett wrote more than 2,000 articles for the Associated Press, covered most wars from Vietnam to Afghanistan and Iraq and won an Emmy Award for his live coverage of the first Gulf War in 1991.

He was the keynote speaker at this year’s Roger Tatarian Symposium, in which Tatarian chair Bradley Martin lauded Arnett as one of the greatest combat correspondents.

“He stayed longer, took more chances and wrote more words read by more people than by any war correspondent in any war in history,” Martin said. “‘No one saw more combat or put himself more on the line.”

Arnett said he didn’t originally intend to become a reporter but applied at his local paper at the age of 17. One of his earliest assignments, while writing for an Australian paper, was covering an axe murderer on the loose who’d been cornered in a standoff by law enforcement.

“When I was in high school, the last thing I imagined being was a war reporter,” Arnett said. “In fact, I wanted to be a musician. But I never did get promoted from the tuba to the instrument I really loved, which was the clarinet.”

Arnett spoke of his extensive history in Saigon as well as all throughout Vietnam, he told of buying his own makeshift materials to stand alongside troops, sticking close to the commander for safety and information.

“At times you will find yourself in combat situations, and at times you should do everything you can to stay alive and unwounded,” Arnett said. “You should know how to swim canals, and ditches are often above your head. If you hear a shot, don’t look around and see where it came from.”

Arnett said that he faced extensive pressures from the American government to report more positive stories in Vietnam. He said that in some instances, Washington was becoming highly critical that he “should get on the line with the rest of the team.”

The job of a newsman, Arnett said, was to cover the news as fairly and completely as possible.

“My stories and others like it angered senior American officials, anxious to keep a lid on the secret war taking place in Vietnam,” he said. “At that time, the Kennedy administration said American casualties in Vietnam were accidental deaths, not caused by combat.”

Arnett said he was told by other reporters to report anything that he saw, including shipments, troop deployments and operational activity, in order to make sure that the American public was informed,and to speak accurately of the realities that troops faced.

“Our concern is to get the news before the public, in front of the public, in the belief that a free public must be an informed public,” Arnett said. “The only cause for which a correspondent must fight is to tell the truth, the whole truth.”

Arnett also spoke about his harsh realities as a reporter both at home in the United States and abroad in Vietnam. He recalled being beaten during a demonstration in Saigon by a surging group of protesters. When he tried to get his bearings, Arnett said, he was forced back down and beaten, his camera destroyed.

“You might think that I was intimidated,” Arnett said. “I had been beaten up by the police. I was under observation. But I was not intimidated, nor were the other reporters. I had felt the wind in my sails, as did my colleagues both American and Vietnamese. The hankering by officials was nothing compared to my growing awareness that I was doing the right thing — that I and the other reporters had consequential roles to play in the growing drama of South Vietnam.”

Arnett said that he was continually motivated to keep going on due to his duty to the public as an eyewitness to history “to record as accurately as possible what we see. That’s what we were being paid for.”

“Many of the more than 2,000 stories I wrote for the Associated Press are eyewitness accounts of battles of the soldiers and officers involved,” Arnett said.

Arnett told stories of his colleagues, as well as his own near-death experiences on the field. Cpl. Frank Gillford of Philadelphia was one marine he quoted, whose wife wrote a letter to the newspaper decades ago.

Arnett said that Gillford’s wife was worried hearing stories from the war, but that he had written his account, a soldier’s account, that American soldiers were not receiving enough credit for their sacrifices in Vietnam.

Arnett spoke of his “band of brothers,” journalists, photographers and reporters as well as the soldiers throughout the years that he had befriended. One of the wives of a fallen colleague, Arnett said, wrote to him about his work in writing.

“You gave the children a legacy no one else could have, and his heroism will live for them, and be an inspiration to them forever,” Arnett quoted.

“I thought it was such a powerful lecture, and I was honored to have attended and hear from the perspective of Peter Arnett,” said mass communication and journalism student Janet Zaragoza. “When he showed the photograph of all the AP press group and mentioned that he was the only one still alive, through everything he discussed and the dangerous situations he faced along the way, it made me admire him in the sense that he was fully dedicated as a correspondent to deliver what was considered to be the truth. Not once did he mention in the lecture that he would give up to deliver the story.”

In his lecture titled, “Young Reporters Defying Old Press Doctrines,” Arnett said that covering the war was an unforgettable confrontational experience that shaped both his and all of his colleagues careers.

“Vietnam was America’s largest uncensored war, and we journalists were pushed between a rock and a hard place, brow beaten by government officials to present their optimistic views, their optimistic version of the war, while the news industry jettisoned the backbone and demanded that we report the unvarnished truth,” Arnett said.

“We chose the truth, sharing with our audiences the distant realities of an unwinnable war that the Americans and South Vietnamese fought, that came to an unbearable heartbreaking end 40 years ago.”