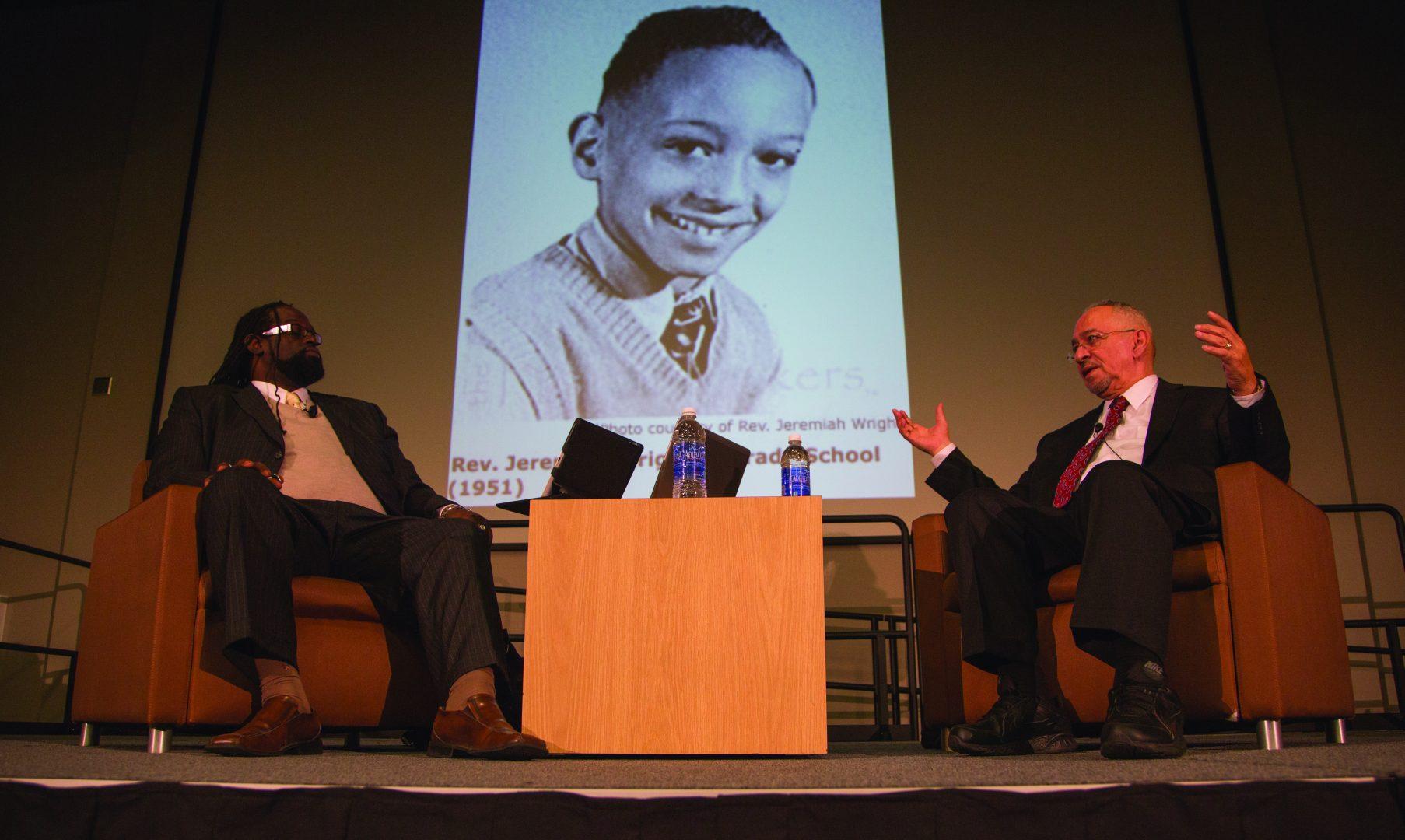

The Rev. Jeremiah Wright, whose relationship with then-presidential-candidate Barack Obama drew media attention during the 2008 elections, spoke at Fresno State Monday night to a packed crowd at North Gym Room 118 about race issues and the role of the church in modern day life.

Appearing as a series on black popular culture and part of African Peoples’ History Month, Wright was an emeritus professor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago and former pastor for President Barack Obama.

Known as a controversial pastor, Wright made headlines in 2008 when a sound clip was released by the media in which he made comments some found inflamatory about 9/11 and American government.

Despite being widely known for his affiliations with the Obama family, Wright’s talk largely centered around stories about his life growing up in segregation, his affiliation and personal relationship with the church and of a growing divide between Millennials and his own generation.

Wright grew up between two homes traveling between segregated Virginia and Philadelphia.

“Most people in this room don’t even know what a slop jar is,” Wright said.

He spoke about his own reality with segregation, witnessing firsthand decades of inequality and racism.

“Once we got south of the line, everything was segregated. We knew before we got to D.C. we would have to go out in the woods to use the bathroom,” Wright said. “I grew up seeing segregated water fountains, segregated drug counters, segregated restrooms, and, when I got to college, segregated beaches. I used to look at the line, and try and see the difference between the white water and the black water. I knew segregation up close and personal and didn’t understand it.”

Wright recalled growing up with a heavy emphasis on education, an education that he said his family taught him to appreciate. His mother finished her undergraduate degree at 17, earned her first masters degree at 19 and second at 21. His father was a highly educated scholar as well, attending seminary school.

Wright developed a growing discontent regarding church practices, and became dissatisfied at an early age seeing Christian churches that were also segregated, like the Richmond Polytechnic group.

“I hear you, angry with what white racists have done to Christianity. I hear you, angry with what the Renaissance did with those false pictures of Italian artists and Italian models. I hear you, angry with what Constantine did… I have a feeling that you love the church, but are angry at what the church has become,” he said.

Wright knew he had an aptitude for religion, but said he had sworn he’d never become a pastor due to his anger with the modern church.

“I wanted to teach seminary, history of religion — swore I’d never be a pastor, because I saw how they treated my father with all his degrees.”

Forty-three years later, Wright recently celebrated his anniversary as a former pastor at Trinity, where he helped grow the church congregation from a few hundred to 8,000, starting programs within the community for HIV patients, student outreach and a women’s center.

“I like in his church the images are all images of color. So the young looking at those images will have a strong sense of who they are,” said Walter Brooks.

Wright noted that many growing up in the inner city never had the opportunity to see a lawyer or a doctor in a personal setting. Not being able to even see these people or communicate with them, how were they to aspire to become them, Wright asked.

Wright explained the context of the soundclips that embroiled him in controversy during Obama’s campaign, calling the media’s actions, specifically those of Fox News, highly egregious and damaging to his family.

“What most people didn’t know, I was not actually in the church when the media started this. I was retired. I had been gone,” Wright said. “And they came to the church, each of them spent $4,000 buying 20 years worth of tapes to see what Obama had been listening to for 20 years and took snatches of it out of context to try to scare voters away from having a black man in the White House.”

Wright spoke about the power and influence of modern media, noting that his parent’s generation lived and died without television in their homes.

“My mother would roll over in her grave if she could hear what our teenagers heard today —

if she could hear Lil Weezy, if she could hear Nicki Minaj,” Wright said.

“The difference is we are losing a lot of Millennials who think the church is full of crap. They have preachers from L.A., preachers from Detroit, everybody talking about getting rich. Many Millennials want nothing to do with the church. They don’t see the point.”

Wright calls iconoclasm and the pursuit of wealth rather than knowledge an instrumental role in the aspirations of modern youth.

“The young people, their theology contextually they get from hip-hop,” Wright said. “They get their theology from Salt-N-Pepa, from hip-hop and we got it from Sunday school. What the church is saying is they aren’t speaking to their reality at all, in any form that they can recognize or connect with.”

He said that even the nomenclature that is used today and taught in schools is wrong.

“‘Transatlantic slave trade’ — you blaming the ocean for the slave trade?”

Part of the problem prohibiting a unified engagement within the black church and congregation, Wright said is a lack of community.

“Today, we don’t see ourselves as a part of the community,” Wright said. “And a part of the so-called integration or desegregation was us moving away from the community, to suburbs or condos where we have nothing to do with the community. Our churches in the suburbs don’t have anything to do with the inner city, they moved away from that element.”

Ebony Brown, an audience member, spoke about her personal disconnect from the church, and said that the black church does not meet the needs of its people.

“I always felt like church was something that we went to. We sung our songs. We hid our problems under our makeup and our nice church clothes. We dressed our kids up nicely, stayed there for an hour or two and went home, but it never hit home.

“So I’m wondering did it ever hit home, or did I just miss something? So I had to leave the church. But within my personal walk, I have stumbles, and that’s where I think the church should lie. Did the church ever meet the needs of the people? Do they understand the struggle?”

Miracle Fauli-Garibay, a senior communications major, said she was inspired by Wright’s talk, in particular his views on the importance of student political participation.

“He said everything that needs to be said, especially to the African-American community, not only towards us, how it’s very important to know more about Christianity and conflicts that come with it.”

As a Millennial, Fauli-Garibay said, she also notices the disconnect and divide.

“I can relate to what he’s saying, being distracted by the media. As young people, we see these images, and they are ingrained into our brains, and we feel like this is the way it is, and it’s not the way it is. It’s not the money. It’s not this. It’s about forming and teaching our community rather than trying to be the best basketball player or the next hip-hop star. It’s more important to inform than to entertain.”

“He’s a modern day Sojourner Truth, truthsayer, and there’s a price to pay when you’re telling the truth,” said Homer Greene.